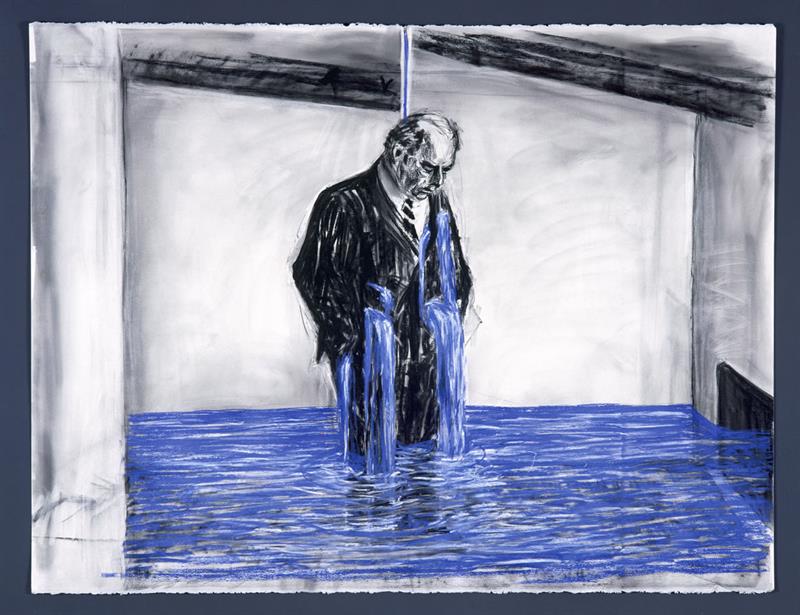

William Kentridge,

Drawing for the film Stereoscope

Charcoal and pastel on paper

120 x 160 cm

Courtesy of the artist

STEREOSCOPE

(Text and interview for MoMA brochure; Stereoscope premiered at Museum of Modern Art, New York, Tuesday 13th April 1999.)

William Kentridge's filmed drawings, or drawn films, inhabit a curious state of suspension from static to time-based, from still to moving. These "drawings in motion" undergo constant change and constant redefinition, while the projection of their luscious charcoal surfaces somehow retains an almost tangible tactility. Smoky grounds and roughhewn marks morph into an incessant, though not seamless, flow of free association that evokes the fleeting hypnagogic images that precede sleep. Bodies melt into landscape; a cat turns into a typewriter, into a reel-to-reel recorder, into a bomb; full becomes void with the sweep of a sleeve. The allure of Kentridge's animations lies in their unequivocal reliance on the continuing present, in the uncanny sense of artistic creation and audience reception happening at once.

Kentridge's films owe their distinctive appearance to the artist's home-made animation technique, which he describes as "stone-age filmmaking." Each of his film-related drawings represents the last in a series of states produced by successive marks and erasures that, operating on the limits of discernibility, are permanently on the verge of metamorphosis. The animations are painstakingly built by photographing each transitory state, as traces accumulate on the paper surface, each final drawing a palimpsest containing the memory of a sequence. The result is a projected charcoal drawing where the line unfolds mysteriously on the screen, with a will of its own, the artist's hand unseen. In the 1950s, filmmakers Stan van der Beek and Robert Breer's time paintings sought to document the creation of paintings on camera. But rather than relating to this moment in film history that looks to performance and kinetic art, Kentridge's films evoke the late silent cinema of Russian and German Expressionism, most directly in the predominance of black and white, the absence of dialogue, and the use of intertitles.

Kentridge lives and works in Johannesburg, where he was born in 1955, in a South Africa ruled by an repressive conservative state. Describing his childhood background as "a comfortable suburban life," he sees himself as "part of a privileged white elite that has seen and been aware of what was happening but never bore the brunt of the might of the state." [World Art p. 48] His films are deeply affected by the landscape and social memory of his birthplace, and allude to his country's struggle to overcome the divisiveness of apartheid. Embedded in the events which unfold as Kentridge's marks materialize is an undercurrent of references, accessible in varying degrees depending on the viewer, to his country's contemporary social history. "I have been unable to escape Johannesburg. The four houses I have lived in, my school, studio, have all been within three kilometers of each other. And in the end all my work is rooted in this rather desperate provincial city. I have never tried to make illustrations of apartheid, but the drawings and films are certainly spawned by and feed off the brutalized society left in its wake. I am interested in a political art, that is to say and art of ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures and uncertain endings." [in William Kentridge: Drawings for Projection, Four Animated Films. Johannesburg: Goodman Gallery, 1992, n. p.] Kentridge's work has always avoided the prescriptive approach of propaganda, drawing on uncertainties and vacillations, the abolition of apartheid having dissolved previously manichean oppositions.

Kentridge's most recent animated film, Stereoscope, is the eighth in a decade-long series featuring the same evolving character, Soho Eckstein. A possible surrogate for the artist, Soho also suggests the archetypal businessman, for he can always be identified by his pin-striped suit. The stereoscope is a device which makes images appear three-dimensional by presenting each eye with a slightly different point of view of the same scene. In attempting to reconcile the difference, the eye is tricked into seeing volume. In Stereoscope, the artist employs a reversed maneuver, where the use of a split screen device can be seen to dismember three-dimensional reality into complementary but unsynchronized realities. In the following interview made on February 22, 1999, William Kentridge discusses the making of Stereoscope and its relation to his other films: [click here to read interview]